Extractive Industries

The rich and varied mineral deposits which underlay the landscape of the British Isles have been exploited for as long as there has been evidence of settlement. From the earliest traces of mining and smelting ironstone on Prehistoric Exmoor to the large opencast mines of the 20th century, the challenge of reaching the mineral deposits, extracting them and transporting them to the surface have remained the same.

As early as the first century AD, the Romans developed a technique known as Hushing, in which a large head of water was accumulated in tanks at the top of a slope and released suddenly, washing away the top soil to reveal the bedrock and any gold-bearing veins below.

Utilising the natural topography of the landscape was also the key to early coal mining, which could only take place in areas where the horizontal coal seams ran close to the surface. Adit or drift mining accessed the coal seams by cutting a near horizontal shaft into the base of a hill, thus removing the requirement to dig down to great depths. Adit shafts were generally cut at a slight angle which meant that the water which accumulated during the mining process drained away naturally.

Where the coal lay on flat land in seams close to the surface, it could be accessed by cutting a ‘bell pit’, a form of mining which originated in the 14th century. A vertical shaft was sunk to reach the coal and the base of the shaft excavated to win the coal, forming the distinctive ‘bell’ cross section. The coal and spoil were winched out, much like a well and each pit was abandoned when it reached the point of collapse and a new pit started nearby. These pits had no system of drainage and often flooded.

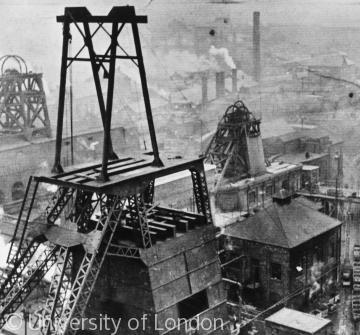

The problem of drainage ensured that mining could only take place on a relatively small scale until the 18th century. The advent of the atmospheric pumping engine and subsequent improvements to its efficiency allowed collieries to pump water and draw the won minerals from greater depths leading to a rapid expansion in the number of coal mines and their scale, which in turn drove the Industrial Revolution. Deep shaft mining, with the distinctive winding gear for drawing men and materials to the surface became a feature in the English landscape from the mid-19th century, with many new settlements created to house the miners in the remote coalfields. The mining of metal ores, which ran in vertical rather than horizontal seams also expanded with the development of steam technology with Cornwall becoming the centre of copper and tin production. Large open-cast quarries also became more numerous during this period, quarrying slate, stone and chalk for construction materials and china clay for the pottery industry.

Following the UK Miners Strike of 1984-85, a response to the planned closure of a number of ‘unprofitable’ pits, the coal industry went into terminal decline. Privatisation could not save the industry and by 2009, there were only four deep shaft coal mines left in Britain.