Distributive Trades

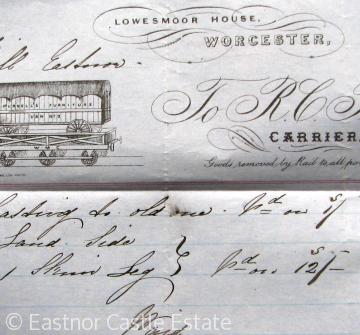

Headed paper of R.C. Purnell, carrier, Worcester, 1861

Headed paper of R.C. Purnell, carrier, Worcester, 1861Goods need to be transported between producer, wholesaler, retailer and customer. Some producers or purchasers arranged their own transport, but many relied upon carriers. At first using strings of packhorses or heavy long carts, by the 17th century enterprising carriers had established regular routes served by stage-wagons. In 1691 an Act of Parliament required the Justices of the everywhere ‘to assess and rate the price of all land carriage of goods’ within their area. This measure, designed to prevent wagon owners combining to push up rates, continued right up to 1827. Such common or public carriers were required to carry whatever goods were offered to them to any destination along their route and to do so at ‘reasonable rates’.

As roads improved, the costs of wagon transport fell and the size of loads increased. Journey times were cut by a third or more by the 1840s. By then there was a dense web of stage-wagon routes from town to town. Although many services were operated by small men, handling one or two short-range routes, others included regular services linking London, regional capitals and market towns.

This expansion of stage-wagon services had taken place in the same period as major efforts were being made to improve river navigation, companies being formed by Act of Parliament for the purpose. By 1730 about 1,160 miles of English rivers were navigable by light craft. Within thirty years a great canal boom was under way. River transport had been ideal for heavy loads such as stone, coal and grain but the network of canals gave greater flexibility. Promoters of the Herefordshire and Gloucestershire Canal stressed that it would bring coal and ‘the sugar and other articles of grocery, iron and ironmongery goods, Manchester goods, furniture, pottery, glass, cheese’ currently brought by stage-wagon and do so more cheaply. Local ‘Canal and General Carriers’ competed with national companies like Pickford and Co., which had begun as wagon carriers in the 17th century and owned a fleet of canal barges by the 1770s.

By the early 19th century the importance of the canal was waning, as the cheaper, faster railways were built. The railways provided the means of carrying the output of factory and prairie more cheaply and in quantity too - the 88 million tons of railway freight carried in 1860 had leapt to 508 million tons by 1910. Carriers by land now served as local distributors to and from the railway stations. Each market town had its own carrying system, dictated by topography, distance and the size and variety of the market itself. That a village had its own railway station and even a shop or two did not mean that it would not have a carrier.

Such villages were also served by town-based hawkers who travelled out to the village with pony or donkey-cart. At the 1851 Census there were in England some 26,000 hawkers, licensed to distinguish them from vagrants. Their number would rise to 69,000 by 1911. Peddlers, even humbler carriers, took their goods far out into the countryside on their own backs, opening their packs of pins, ribbons, lace or combs, brooms or mats at their customers’ very door. This was a real blessing in an agricultural area, for farm labourers, live-in apprentices and the many girls and young women in domestic service, 900,000 of them at the 1851 Census, had few leisure hours and those not on market days. Not only did hawker and peddler bring the market to the customer, they also broke down the cost of their goods either by selling piece-meal - half rather than a whole sheet of pins or needles - or by selling larger items on instalment.

By the early years of the 20th century steam wagons and motor vehicles were providing the motive power for distributing goods. But even in 1909 there were only 154,000 registered motor vehicles in the whole of Great Britain and 832,000 horses still employed in haulage. It was the First World War which really fostered technical advances in the motor vehicle, encouraged its production and required large numbers of men to train as drivers and motor mechanics. The end of the war in 1918 released a great array of ex-army lorries going cheap and men war-trained to drive and maintain them used their gratuities to buy many of them. This new form of transport, now threatened village carrier and railway alike. It had much of the flexibility of route of the one and was cheaper than the other. The motor-bus was not only a public people-carrier, but also functioned like village carriers, often following the same routes from village to market town, collecting and delivering parcels on the way.

Shops began offering ‘deliveries by Motor Van to all parts of the district once every week.’ Such vans were capable of penetrating much deeper into the hinterland than slow-moving horse and cart had done and light vans, used by manufacturers, traders and shopkeepers for their retail deliveries formed some three quarters of the 128,200 goods vehicles in Britain in the early 1920s. National companies like Sutton & Co., who had long specialised in parcel deliveries, also motorized, expanding to some 600 branches.

By the second half of the 20th century, Dr. Beeching had wielded his axe, drastically cutting rail-track mileage and in more rural areas closing up to two thirds of their stations. By then buses too had lost up to half their passengers and had long ceased to carry goods. The 1981 Census showed that journeys to work by public transport had fallen by over a third since 1971. The gainers had been the private motor car and the fleet lorry companies. Ever larger articulated lorries carry containers of goods from ports and manufacturers to distribution centres. From there the goods are taken to the retailer – even in 2009 the average length of haul within the UK was only 58 miles. The final distribution from shop to home is now largely the responsibility of the consumer - as car owners in a self-service world, we have all become carriers.