Industry

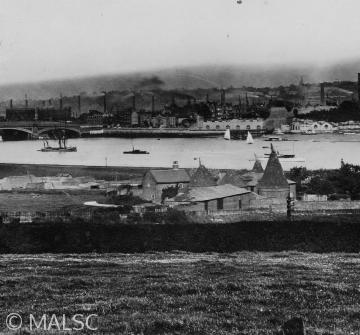

A view towards Rochester from Strood showing the variety of the Medway Valley's industries

A view towards Rochester from Strood showing the variety of the Medway Valley's industriesAlthough associated by many primarily with the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries, industry can be broadly taken to mean the manufacturing of goods or an area of economic production.

Exploitation of England’s mineral wealth, the working of metal, production of cloth and material from the indigenous sheep population, leather working, production of pottery, brewing and the production of foodstuffs, in an organised and large scale can all be traced back to at least the Roman occupation of Britain.

By the time of the Norman Conquest, skilled craftsmen tended to form organisations based on their trade or craft. In organisation and operation these ‘Guilds’ were somewhere between a trade union and a secret society, protecting the interests of the craftsmen and ensuring a good price for their wares. Guilds were at the centre of organised manufacturing in England until the end of the 16th century, leaving their mark on many English towns in the form of Guildhalls.

During the 17th and early 18th century, industry in England is perhaps best described as organised manufacture. Often termed “putting out” or cottage industry, labourers were provided with the raw materials by the entrepreneur and worked on them at home with the finished product collected, taken to market and sold, the labourer being paid by the ‘piece’. This system of industrial production was most commonly found in the textile industry with spinning and weaving taking place in the home, although boots and shoes, nails and chains and pottery production were all also cottage industries at one time.

Industry in its modern context is best surmised by the shift from small scale manufacturing to large scale mill and later factory production. Entrepreneurs soon realised that cottage industries were slow and inefficient, governed by the pace of work that each family unit could work at. Technological innovations, initially in the textile industry such as Arkwright’s Water Frame (a water powered spinning frame patented in 1769) and Cartwright’s Power Loom (an initially water but later steam powered weaving loom of 1784), allowing the textile industry to be moved from the home to the factory. The factory system and was considerably more efficient with raw materials coming in and finished products going out in bulk. The use of candlelight and later gas lighting meant that working hours could also be extended and productivity further increased.

The factory system also affected the English Landscape and settlement pattern. Jealously protective of their inventions and reliant on waterpower, industrialists built the early mills in remote, rural locations and were forced to build accommodation for their workforce.

During the 19th century, the speed of technological progress quickened, water power was replaced by steam power and output rose at unprecedented rates. The iron industry and the increasing number of steam engines created a massive demand for coal, transforming relatively small scale surface mining to deep shaft mining on a truly industrial scale, complete with colliery villages and transportation networks. The transportation of coal on railed wagonways also led directly to the birth of the railways which replaced the canal network as the principal mode of goods transportation in the mid-19th century, establishing the rail network which is still in place today.