Trade and Commerce

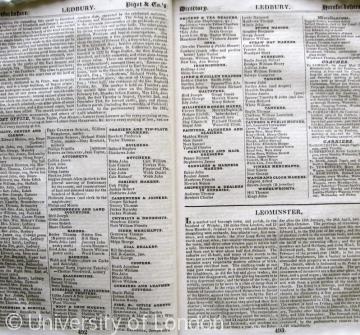

Pigot's Commercial Directory, 1830 for Ledbury, Herefordshire

Pigot's Commercial Directory, 1830 for Ledbury, HerefordshireThe exchange of goods between people is of great antiquity. Archaeologists have found stone axes on prehistoric sites far from their origins, though the process by which they were exchanged is lost to view. They may have been passed through a series of hands, as gifts, tributes or commercial commodities, exchanged in return for some other goods (barter). Some societies developed a system of using livestock or grain as a form of currency; others used certain stones or shells. When Julius Caesar invaded Britain in 54BCE he noted scathingly that the natives were still using sword blades as currency, though in fact Celtic tribes had been using coins made of gold, silver and bronze for some time. The production and control of currency has a major impact on the ease or difficulty of commerce and has been regulated by royalty or the state since Anglo-Saxon times.

Historians are now aware that trade and commerce played a much larger part in medieval life than was once believed. Very few peasant households were entirely self-sufficient, even in foodstuffs. They had to buy clothing and tools and regularly bought foodstuffs, whether butcher’s meat, fish, pies and puddings or more specialist items like salt or spices. The international trade in spices and silks may have left more trace in the historic record, in the account books of merchants or in taxation records, but the small-scale trade in basic foodstuffs and the necessities of daily life encouraged craft and agricultural specialisation and production for the market. This trade fuelled the great expansion of the 13th century and influenced economic development after the Black Death in the mid-fourteenth century.

Towns (sometimes with only a few hundred people) developed where people practised a range of trades and offered a variety of services. Customers visited craftsmen at their work shops, bargains were struck between producers and purchasers in many places, including inns. Village craftsmen, too, supplied their neighbours’ needs, working in wood or metal, and enterprising villagers took local produce to market, returning with town-made items for resale.

The pace of commercial life began to change from the later 17th century in England, with the introduction first of paper bank notes (1660s) and the establishment of the Bank of England (1694). International trade also quickened under the stimulus of increasing population at home and developing colonies abroad. At this period there was a strong belief in the need for strict regulation of agricultural and industrial production as well as the use of customs tariffs to control the international movement of goods and especially bullion. This ‘mercantile system’ was criticised by Adam Smith, who opposed the notion of control and believed in a free market economy. The debate continues.

The great ebbs and flows of economic cycles (and the theories which go with them) are properly the province of economic historians. Detailed studies of local economies, particular trades or even of individual enterprises need to be seen in the context of these broad movements. In turn, these local studies can add nuances to theoretically driven histories.