Transport and Communications

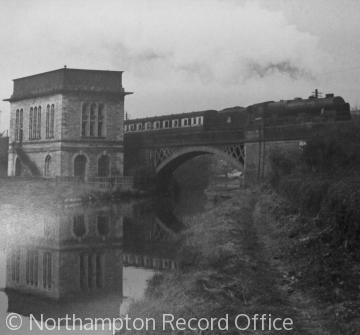

The Grand Union Canal and railway bridge at Blisworth, Northamptonshire

The Grand Union Canal and railway bridge at Blisworth, NorthamptonshireCentral to the history of England and the development of the English landscape is the network of communications and transport links which connected dispersed and nucleated settlements, allowing revolutions in agricultural and industrial production and prompting the dramatic growth of England's towns and cities.

Evidence of Prehistoric and Roman attempts to link areas of settlement can still be seen in the modern landscape and traced using historic maps. Long linear tracks, paths and features which appear to follow elevated ridges and cut across man-made elements of the landscape may indicate ancient routes. A small number of these very ancient routes survive in the modern landscape as walking trails, such as the Ridgeway, a Neolithic track way which once linked Dorset with Lincolnshire, although only some 85 miles remain.

The Romans, synonymous with road building, constructed the first national communications network, laying c.2000 miles of surveyed and paved roads to allow the efficient movement of troops and military supplies around occupied Britain. Although it is unlikely that maintenance of these roads continued after Roman occupation, they remained at the heart of transport in Britain throughout the medieval period and some stretches of the major arterial routes were eventually incorporated into the modern road network. Stretches of Watling Street (which linked Dover and Wroxeter via London) form parts of the modern A2 and A5, while sections of the Fosse Way (which linked Lincoln and Exeter) can still be traced on the A37 in Somerset and the A46 in Leicestershire.

Although transport between centres of settlement remained important throughout the early medieval and early modern periods, especially with reference to the movement of agricultural produce and livestock between the rural hinterlands and market towns, it was not until the 18th century that a systematic attempt was made to improve Britain’s roads and inland waterways.

Tudor statutes had placed responsibility on individual parishes to maintain their roads, but little provision was given to major arterial routes and as trade and the need to move goods to London increased, the principal and poorly maintained routes could not cope with the increased level of traffic. A solution to the problem of maintaining a road that ran through several parishes was to erect tollgates on sections of the highway to collect revenue from users of the route. This revenue was held by a trust that in turn used it to ensure the road’s maintenance. Between 1707 and 1825, over 1000 Turnpike Trusts were established controlling over 18,000 miles of routes.

Contemporary to the development and growth of turnpike roads was the establishment of the canal network. Goods had been carried to major centres of trade by river barges since the medieval period, but the navigability of England's rivers varied greatly and the need to transport delicate goods such as pottery and raw materials in bulk, such as mined coal from isolated rural areas to ports and cities, led to the construction of artificial canals. The first of these was commissioned by the Duke of Bridgewater to link his mines at Worsley with Manchester to satisfy the growing appetite for coal following the mechanisation of the cotton spinning industry, which duly opened in 1761. Between 1770 and 1830, with demand growing for efficient movement of freight, the canal network grew to nearly 4000 miles and included a number of engineering triumphs.

However, following successful attempts to harness high pressure steam and convert steam power into locomotion to pull coal wagons, railways quickly evolved from their predecessors, the wooden wagon ways of the northeast coalfields, to surpass the canals and turnpike roads as the principal means of transporting goods and people around the country. In some cases, the canals were obsolete before they were completed and at Strood, the canal was converted into a railway with the rails running on the canal towpath and on piers in the water.

The canals and then to a greater extent, the railways, united the villages, towns and cities of England, Scotland and Wales in a way that the road system had not. In addition to facilitating rapid expansion in boom towns like Manchester and Birmingham, they spawned entirely new settlements, located so as to be close to the transport network. Swindon and Crewe evolved as newly created centres of locomotive manufacture, while Sir Titus Salt moved his entire wool spinning operation and workforce to a new site close to both the Leeds and Liverpool Canal and the railway, creating a new settlement, Saltaire in the process.

Between 1830, when the Liverpool Manchester Railway was completed and the end of the Second World War, Britain relied heavily on the railways but a plan to create a network of high speed routes conceived during the war, changed the transport priorities. A surplus of lorries and trucks in the years after the war and the increased availability and affordability of the privately owned motorcar proved too great a competition for the freight and passenger lines and in the wake of the birth of the motorway network in 1958, the railway network was dramatically reduced from 1963.

In the 21st century, road transport is king but the railways still play an important part, whereas the canals have seen somewhat of a renaissance in line with the growth in popularity of the canal boat holiday.

_Aerial%20View%20of%20Newlyn_tourist%20board.jpg)