The Engagement of Churches in Social Welfare and Related Provision in Edwardian Basingstoke - 1903

Prior to the emergence of the Welfare State, churches made a valuable and valued contribution to social welfare provision either alone or collaboratively. In prioritising the needs of others, churches were seeking to give practical expression to Christ’s injunction to ‘love your neighbour as yourself.’ By the Edwardian era this had become formalised in the concept of ‘the social gospel’ with adherents claiming that ‘good works’ were as legitimate a pursuit for the churches as the saving of souls. Drawing upon examples from Edwardian Basingstoke during a single year, 1903, three main forms of church engagement in social welfare can be identified.

First, there was the sponsorship of slate clubs, which were essentially savings/insurance schemes to assist members in times of financial need, such as sickness. Here a good example was the club sponsored by London Street Congregational Church’s Pleasant Sunday Afternoon Society. Established in 1901, 366 members joined the club during 1903.

Second, there was fund raising for good causes. In January, a two day bazaar and entertainment was organised by the Young Helper’s League to raise funds in ‘support of a “Basingstoke Cot” ’ at the Stepney Causeway homes of Dr Barnardo. A second example, was a concert given by the members of the Bethesda Male Voice Choir in May. This was a cross-denominational initiative, with the aim being to raise funds to ameliorate the suffering of the Penrhyn Quarrymen, who were on strike, and their families.

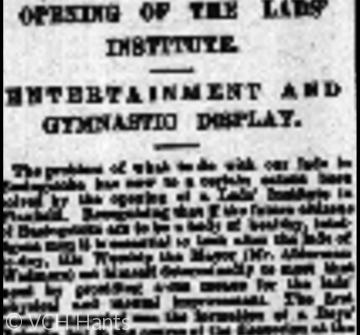

Third, there were various kinds of what may be loosely described as ‘direct action’. One involved the establishment of a Lads Institute prompted by what was seen as a duty to provide ‘some form of attractive and healthy recreation, combined with a modicum of useful instruction, for the lads who … [spent] their spare time in the streets for want of a better place.’ Another was the extensive support given to the cause of temperance seen as a means of alleviating the social distress resulting from the excessive consumption of alcohol. This took a variety of forms, such as campaigning to ban the opening of public houses on Sundays and to reduce the number of licensed premises in the town, and facilitating the work of temperance organisations, such as the Women of the White Ribbon, the Band of Hope, the Total Abstinence Union and the British Women’s Temperance Association. On a smaller scale, following a flower service at the Congregational Church in July, the children’s offerings were ‘sent to the Cottage Hospital, the almshouses, and to the Flower Mission.’ Similarly at Harvest time the Cottage Hospital received gifts of flowers, fruit, vegetables and cash from a wide variety of churches in the neighbourhood.

As these examples illustrate, without the involvement of churches, life in Edwardian Basingstoke for those disadvantaged and or in need would have been poorer. By giving attention to ‘good works’, church members sought to make a difference and although on issues, such as temperance, there would have been strongly held differences of view within the community, at the very least churches were motivated by a desire to ensure that spending on alcohol was not at the expense of the wellbeing of family members, particularly women and children.

(For the source of the quotations please see the asset)

Roger Ottewill

March 2019

Content derived during research for the new VCH Hampshire volume, Basingstoke and its surroundings.