Westminster Road Semaphore

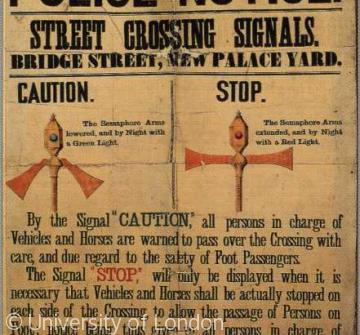

By the 1860s, railway signal boxes had become one of the most conspicuous structures of the rapidly changing landscape of Victorian London. Their size reflected the scale of incoming and outgoing flows of goods and people affecting not only railways, but also the river Thames, canals and key thoroughfares. The regulation of these flows concerned accommodating their constant growth as well as securing the safety of connections across several modes of transport. Late in 1868, Saxby and Farmer, railway signal engineers of the London Brighton and South Coast railway, built a composite of ‘semaphore signals and coloured lights […] to regulate the street traffic’. The semaphore was erected at the intersection opposite Palace Yard of the newly rebuilt Houses of Parliament. It consisted of a pillar fitted with three arms facing Bridge Street, Great George Street and Parliament Street that were operated by a constable. The experiment was successful if short-lived. A series of gas explosions early in January 1869 caused by a leak in one of the mains underneath the pavement injured the constable in duty raising doubts about the mechanism’s safety [1]. The experiment was abandoned and revived once the first electric signals made their appearance in the 1920s.

The proponent of the street semaphore was John Peake Knight, at the time traffic superintendent of the South Eastern Railway. Knight’s idea rather than creating new layers for continuous traffic, such as the increasingly convoluted network of underground and overground railways that had been built by the late 1860s, lay on directing flows at street intersections by introducing intervals for pedestrian crossings in order to secure a ‘regular stream of traffic’ along busy roads. During the hearings of the Select Committee on the London (City) Traffic Regulation Bill in 1866, Knight used the example of the Parisian sergeants de ville, as an illustration of the relative success of stricter rules for traffic and the consequent gains for the safer movement of pedestrians, horse-drawn vehicles and cart drivers. The street semaphore encapsulated an innovative way of looking at the circulation of people, animals and vehicles, which was based on Knight’s long experience with railways and according to which flows could be regulated in terms of their speed and direction as well as their place within a route hierarchy, all three key features of how we understand modern road traffic today.

For a vivid impression of the ebb and flow of early twentieth-century London streets see the four-minute clip ‘Old London Street Scenes’ (1903) available from the British Film Institute YouTube channel at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v-5Ts_i164c

[1] For a brief report on the gas explosions see ‘Westminster Street Semaphore Signals’, The Times, 6 January 1869, 10. For a detailed description of the semaphore see ‘The Perils of the Streets.-A Novelty in Signals’, The Illustrated Police News, 12 December 1868.

Content derived from research undertaken as part of the Victoria County History project