Market Day

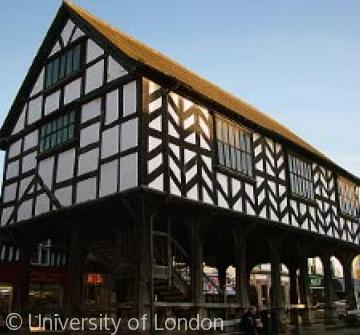

Market Day in Ledbury ‘The farmers used to bring their animals through to market…through the town. The sheep and the cattle. They used to have a trough of water out there for the animals to drink.’ 1 Ledbury was no more than a village in 1068. Its important church served a wide district and it was only natural that attendance at church should be combined with all sorts of marketing. The first recorded Ledbury market charter was issued by King Stephen to Bishop Robert de Bethune in 1138. ‘Know that I grant Robert, bishop of Hereford, may have a market on Sunday of each week in his manor of Ledbury’. Each Sunday, and on the great days of the Christian calendar, Easter, Whitsun and Christmas, the Lower Cross and the lane leading up to the church would be the scene of intense activity. The area would be full of cattle, sheep, poultry, and farm produce of all kinds. Specialist craftsmen and pedlars would vend their wares. Church Holy Days became market and fair days and holidays. Later, the church authorities discouraged trading on Sundays, and Monday became the market day in Ledbury. On market and fair days the High Street would have been filled with stalls, goods and animals. Originally these stalls would have been erected for the day and taken down, under the close supervision of the bishop’s bailiff, at the end of the day. John Stow in his Survey of London, 1598, describes this: ‘In old Fish Street the houses, now possessed by fishmongers, were at the first but moveable boards (or stalls), set out on market days, to show their fish to be sold; but, procuring licence to set up sheds, they grow to shops, and by little and little to tall houses, of three or four stories in height, and now are called Fish Street’. This market encroachment, as it is called, is still to be seen in many of our market towns. In Ledbury, even by 1288 the temporary stalls and booths were giving way to permanent structures, rents for for five shambles (slaughterhouses) and fourteen seldae macetarie (butchers’ stalls) being paid to the Bishop. This represents the origins of the Butcher’s Row a narrow row of shops running north-south along the High Street. With the rapid growth that took place after 1120 the High Street (known as Middletown) was no longer large enough to cope with the requirements of expanding markets and annual fairs. In the middle ages it was common for one or more of the major roads, either within or just outside the walls or borough limits, to be used as overflow market areas. In Ledbury, Bye_Street became a secondary market area. In the early 16th century there is evidence for decline in the prosperity of the market and a number of the properties in the market place were vacant. Matters improved later in the century and in 1584 Queen Elizabeth graned a new charter, allowing a weekly market on Tuesday and two fairs, on the feasts of St. Philip and James (1 May) and St. Barnabas (11 June). In 1617 a group of local citizens bought some property ‘at or near a place called the Corner End’ and here built the new market House [link to Market House item]. After more than 600 years the market encroachment had gone and the market place was, apart from the Market Hall, an open space, as it had been when first laid out in the 1120s. 2 In 1741 Badesdale and Toms’ map of Herefordshire listed all the market towns and the days of their fairs and markets. Market day in Ledbury was on a Tuesday, with fairs on May 1st (St. Philip & St James), June 11th (St. Barnabas), 21 September (St. Matthew), the Monday before St. Luke (18 October) and the Monday before St Thomas (21 December). In the 1870s, a weekly market was held on Tuesday; a great market, on the last Tuesday of every month; and fairs, on the Tuesday before Easter, the second Tuesday of May, the third Tuesday of June, the second Tuesday of August, the first Tuesday of October, and the Tuesday before 21 December. The old manufacture of broadcloth, gloves, sacking, and ropes had declined, and trade was chiefly connected with agriculture, including malting, tanning, and trading of hops, cider, and perry. The Easter and October fairs in the 18th and early 19th C. were renowned for their cheese, with the prices reached being recorded in the Bath Chronicle. 3 A purpose-built cattle market was built to the west of the High Street in 1887. Market Street opened off Bye Street, very close to the Ledbury Town Halt on the Gloucester to Hereford railway line. Although the sales now took place ‘off street’ many beasts were still driven through the town to market. Descriptions of Market Day 'Market day used to always be a Tuesday, livestock market, and nobody ever made an appointment but they would expect to see someone, preferably the boss, whatever happened. So Tuesday was always a very busy day in the office. Nowadays people ring up and make appointments weeks ahead but that didn't happen then. Market day was always a busy day, because the other thing was that a lot of the livestock used to be driven down the road. We had to keep our gates closed. You'd get a flock of sheep in here or something. And of course a lot of the stock used to come by train in those days, before the war. If you look at the right, just under the railway bridge - I don't know whether you can still see but there used to be a siding there where they'd back the cattle wagons in, and the cattle used to come bounding down there and then they'd drive them loose down to the cattle market. If you'd got the gates open here you'd have half a dozen bullocks in the garden! The Feathers, The Talbot, The Ring of Bells and The Brewery, they all had what they called a market day extension until 4 o'clock in the afternoon. 4 'Saturdays and Tuesdays were the main shopping days in Ledbury. Always busy on market day, Tuesday. Farmers' wives accompanied their husbands to town to do their weekly shop and most did their workers and workers' wives' shop too. The other heavy shopping day was Saturday. Before working hours per week were radically reduced, the only shopping day for workers was Saturday and for some, only Saturday afternoons.Oliver Howe ran a private bus company, which served the country areas on Saturdays and Tuesdays. Their rear-loading Morris commercial small coach parked outside the Seven Stars. Arrival and departure times when the passengers were good and ready. The driver was the ever amicable Mr Davies.'5 'There were no stated hours for opening or closing shops and early closing day was unheard of. On market days sheep were penned in High Street, near St. Katherine’s Chapel, and the cattle in the Homend; pigs were penned opposite “Seven Stars”. Posts and rails were fixed to keep cattle from shop windows. Most shops were approached by steps. Horse dealers did a big trade outside “The Feathers”, the horses being trotted up and down High Street; they were also sold in Union Lane [Orchard Lane in 2008] then called Horsefair Lane. On fair days (Mops) it was a common sight to see women and girls on the east side of High Street and the men and youths on the opposite side waiting to be hired. Some farm hands wore a length of plaited whipcord in their hats and those who preferred jobs as cowmen displayed a whisp of horsehair, they wore smock frocks and corduroy trousers/breeches.’6 In Grace Before Ploughing, John Masefield's memories of his childhood in Ledbury, he describes events in the market place and the great impression they made on him as a small boy. Other poems, such as The Widow in the Bye Street and The Everlasting Mercy, also contain descriptions of the October hiring fair and the Ledbury market scene, and evoke the extreme suffering of people living in poverty at the time. As a child John Masefield watched animals and wares being brought into the market place: ‘...the timber-carters were fine, hearty fellows, who made a point of entering the market place with a cracking of whips....The men made a practice of walking beside their teams as they entered the market place, and as warnings to those in the main street they cracked their whips with a skill and noise that encouraged their teams... and the horses responding to the cheer, with their great souls greatly exhorted and the great trees brought round the bend.’ He also describes vividly the great yearly marvel called the October Fair: ‘...It was a hiring fair, where men sought employment for the coming year, and the broad main street was glad with the sports of the fair: swings, merry-go-rounds, and coconut shies. It was busy also with the work of the fair: the sale of beasts of many kinds, which came there looking their smartest, to be judged and tried, in pens in the crowded street in the tumult of noise that made the fair so wonderful. The sideshows ...kept to the west side; the pens of the beasts were east from there. In any clear space men tried the paces of the horses for sale. Under the market building, and in a paven space just south from it, there were egg and cheese and butter sellers, and the cheap-jacks, with their patter, and their piles of crockery. In the road.... men placed wonderful painted zinnias and wooden sticks...By daylight the town began to fill up with those who had come for the fair.’ He describes how people came from far and wide, and the traditional trading of insults between the English and the Welsh. ‘To a little boy, the aspect of the Market Place was one of entrancing interest, noise and glad excitement. There was a mingling of rude music, song and cries of cheer; cheap-jacks were calling their goods, raising loud laughter, or smashing plates when bidders would not bargain for them. Mechanical music came from the merry-go-rounds, and from mouth-organs played by those in the swings. All those who had goods to sell spoke in their wares' praise. All the beasts and fowls from local farms, brought there for sale, added their cries and calls. Horses were being tried for short distances; pigs and sheep were complaining in their pens; and men were praising their wares or their beasts at the tops of their voices....Usually, too, there were mummers, in their traditional costume....Various amusements started when the business had ended: a boxing booth would open for the young men eager to try their skill; others would be tempted to show their strength, by hitting a pestle with a mallet. This was ever a favourite sport with the young men. They would be tempted to have three shies for a penny at Aunt Sally, and...every time you hit you would get a good cigar.’7 References: 1 Oral history interviewee, England’s Past for Everyone 2 Ledbury A Medieval Borough, Joe Hillaby, Logaston Press 1997 3 Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales (1870-72), John Marius Wilson 4 Oral history interviewee, Bill Masefield 5 Ledbury shopping in the 1930s: Pip Powell in the Ledbury Portal 2007www.ledburyportal.co.uk 6 Recollections of Ledbury, G. Wargent, 1905, 34-5 (Writing of the period c 1830 ) 7 Grace Before Ploughing, John Masefield, William Heinemann Ltd, 1966 General: Volume V16, Page 359 of the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica

Content generated during research for two paperback books 'Ledbury: A Market Town and its Tudor Heritage' (ISBN 13 : 978-1-86077-598-7) and 'Ledbury: People and Parish before the Reformation' (ISBN 13 : 978-1-86077-614-4) for the England's Past for Everyone series